How one woman learnt to let go of the bullying in her past by facing it front on – by Carla Caruso

I’m perched on a couch in an incense-tinged side room of a yoga studio. My eyes are closed and I’m nodding as a hypnotherapist softly speaks, encouraging me to cast my mind back to the past. So far, I haven’t been made to dance like a chicken or remove any clothing, like I’ve seen TV hypnotists persuade people to do. The session is actually quite relaxing.

An ad on a deals site has led me down the path of hypnotherapy after a looming book deadline has given me an anxious stomach.

The hypnotherapist asks me to think back to a time when I first felt anxious. Apparently, it’ll help my un- conscious mind release past hurts. “Was it before, during or after birth?” she prods. “I was 11,” I blurt, surprised to find my fists clenching.

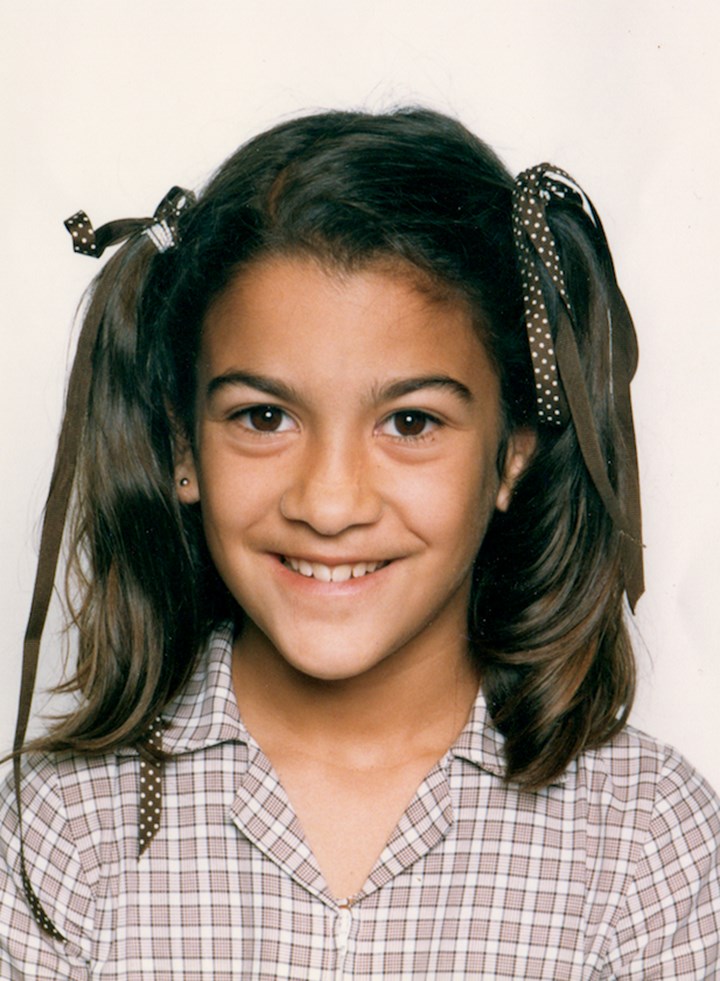

A memory, long buried, has popped into my mind. Of sitting across from a fair-haired boy in year 7 and hearing him loudly remark on my Italian appearance, on repeat. He would call me names like “Moustache” and “The Sun” (the latter due to my olive complexion). Names that sound harmless now but then stung so much that I’d pretend not to hear him and never say anything back.

He was also the kid who snickered that I should have been the one in my group nicknamed “Black Cat”. (My three best mates and I had a club called “The Cats” and each had feline-sounding monikers, which we rather dorkily painted on T-shirts in glitter paint. My name was “Tiger Eyes”.)

The hypnotherapist now urges me to recall a similar experience, even earlier on. My mind reels to two blondes cornering me in the playground and asking what country I’m from. (I went to a very Anglo school in Adelaide’s southern suburbs.) When I answer that I’m from Australia, the girls tell me I’m wrong, to try again. But it’s true; only my mum was born overseas, in Italy.

I should have known that hypnotherapy would catapult me down memory lane, but I’m still taken aback by the recollections that have surfaced. I’m 40 this year, now a school mum not a kid, and being Italian is no longer a big deal. (I even wed a true-blue Aussie.)

Not that racial bullying has gone away. As the decades roll on, it just changes its focus to other ethnicities. But at least awareness of schoolyard taunting has improved. My twin boys regularly come home with anti-bullying paraphernalia, including colourful wristbands they proudly wear.

Anyway, following my hypnotherapy I’m pleased to find the anxious pangs in my stomach have dissipated. However, that night, when I’m in bed, the anxiety is replaced by something else. A burning anger. I toss and turn, reminded of the barrage of racist remarks I once put up with and even felt I somehow deserved for being “different”. I’m fuming for my inner child who was too shy to stand up for herself.

Days later, I receive a message via my author page on Facebook. It’s from an old primary school teacher, asking if I’d be interested in speaking about my time there at the school’s 50th anniversary fete. I can’t think of anything worse. I click on the Facebook page that’s been created to celebrate the anniversary. It’s a horror show of old class photos and memories.

I pause mid-scroll on one washed- out ’80s photo, depicting four blonde girls standing on a wooden log. The quartet symbolised everything I wasn’t, with their flaxen hair, blue (or green) eyes, loud personas, and name-brand fashion.

Aside from my clothes (made by my sewing- enthusiast mamma), my difference mostly boiled down to everything about me being darker. My hair (on my head and body), my eyes, my skin. My two sisters and even my migrant mum don’t remember copping much racism.

Although my mum did say an aunt once told my second-generation dad, “You’ll never get a girlfriend because you’re too dark.” I’m his spitting image.

I remember a younger kid once yelling “Aboriginal Cher” at me across the playground, though we’d never even spoken before. I even named my black Barbie doll after myself because I thought she was just as ugly and different as I was.

As I stare at the picture of the four blondes, I feel something swell inside of me. Could kids like them have known how much their words hurt? The effects that have lingered? Suddenly I know I need to delve into my school past and confront my former bullies.

The first person I search for is the kid who called me “Moustache”. I’ll name him “Pete”. A LinkedIn profile pops up. There’s a studio-style shot of him, sporting glasses and, well, less fair hair. He wasn’t how you’d picture the typical bully, being short, studious and more middle-of-the-road than cool kid. Now he’s in mining interstate.

With my heart in my mouth, I click on “connect”. After refreshing my inbox a few times, and no message to say he’s accepted me (what’s new?), I move on – to one of the blondes. Let’s call her “Gwen”. She wasn’t the group leader, but she was the girl who refused to accept I was born in Australia.

I find her on Facebook and send her a vague message. It’s about now that I’m rethinking my mission. Who wants to admit that they still have hang-ups from school?

To my surprise, “Gwen” replies within seconds, agreeing to a phone interview a few days later. I don’t have a good sleep the night before and feel like I’m about five again. On the phone though, she sounds less like the popular girl who paired her uniform with pink leg warmers and, well, more like me. She now works in real estate in Christchurch and even calls herself “shy”. When I finally ask her about the “incident”, I stumble over my words.

“I’m so sorry,” she exclaims. “Oh my God. I can’t remember saying that.” Ironically, she’s now dealing with her seven-year-old daughter having friendship issues, plus trauma following the mosque shootings nearby. “It’s really opened a lot of kids’ eyes – to be kind and not judge,” she says, admitting that her kids are exposed to a lot more cultures than she ever was.

Buoyed, I work up the courage to phone where “Pete” works next. My call goes to voicemail. I’m not hopeful he’ll ring back, but later I receive a text. “Hi, ‘Pete’ here. Let’s find time to have a chat.”

Gulp. It’s on. Needing to rip off the bandaid, I arrange via text to speak to him that night. Later, on the phone, he sounds like I remember: smart and assured. After some small talk, I get down to the nitty-gritty, reminding him of his past comments. Like Gwen, he doesn’t recall, but says, “Thanks for telling me. That’s terrible. I guess you don’t remember the names you use, only the names you’re called.”

I press on, asking why he thinks he might have done it. “To be honest,” he muses, “I was probably just jumping on what was going around. I didn’t really carry any bad feelings towards anyone.”

For me, it’s cold comfort. Turns out the name-calling that I’ve held onto wasn’t about me, just impressing the pack. I was an easy target because of my otherness.

I let him off the hook by saying he probably had quite the Aussie home life by comparison. But he says, “Not really. My [late] dad was Slovenian and my grandparents spoke broken English.” This means that despite the regular surname and looks, he’s ethnic too. He goes on to lament his father never teaching him Slovenian. “It would have been nice, but Dad was a wog and got picked on at school. He was, like, ‘What’s the point?’”

Oh, the irony.

I move on to “Pete’s” domestic situation now and I’m in for another shock. “I married an Indian-Malaysian lady,” he says, joking a little inappropriately, “So talk about ‘The Sun’, she lives on the sun. We have a little caramel boy.”

In bed, I twist up the sheets again. Strangely, I’m dissatisfied, angrier, after the call. Then a realisation hits me. This is not about forgiving those who called me names — they were just kids being kids, and have all turned out to be lovely people. This is about forgiving myself. I’m just as judgemental of that weird, foreign-looking dork I was. These days, I feel closer to a cool girl. I like fashion. I’ve had an exciting career. Celebs like the Kardashians have helped me appreciate my “exoticness” (aided by laser hair removal).